Who knew? I read the other day how a plague that spread through the Roman Empire created, alongside other havoc, a gladiator shortage. (We’re talking the mid-second century CE.) Worse, this gladiator shortage tickled a connection that ultimately spurred the growth of Christianity.

I’m not well schooled in systems theory, but this could qualify. The classic “a butterfly flaps her wings in Brazil” and way up the line a tornado whips up in Texas. Or maybe that’s because Texans keep voting for more oil and worse tornados.

But back to gladiators, and ultimately to their sanguine effect on the Christian cult. These beefy fighters were usually slaves and war captives owned by a manager. As popular as some of them were, they still spent their non-training hours in chains. Once showtime arrived, they dressed for success; failure was an ugly option (although only 10 percent fought to the death, say scholars. Training gladiators at the empire’s many schools was costly). Gladiators suited up in combos of ornate helmets, arm and leg shields; they carried tridents, weighted nets, and long swords, according to their style of fighting. If you’ve ever seen Spartacus, Kirk Douglas fought Thracian-style (but without the Thracian helmet—I guess so you could see his Hollywood face. Kirk et al also wielded the gladus, the eponymous short sword that meant you got in close.

Speaking of gladiator movies, most gladiators didn’t look like buff Russell Crowe in the first Gladiator, in 2000. Gladiators ate mostly barley, beans, nuts, and seeds, and lots of it—they were sometimes even called “barleymen.” They were better trained than Roman centurions (who also ran on barley). Still, entering the arena bearing some barley-built body fat granted a layer of protection against blades that would otherwise slice too deep. So, to be accurate, most gladiators looked more like 2025 Russell Crowe. (I don’t care. I will watch him in anything.)

Like a lot of life in Rome, gladiators had a hierarchy. Lower-level gladiators called Bestii were expected to hunt, wound, and kill animals—as the bull-fighting Spanish still do today, so fuck you, Spain—or to be hunted and killed by them.

And those battling weren’t just men. Emperor Domitian (81-96 CE) liked to watch women gladiators fight dwarves. It is unclear whether these DEI fights starred average-sized women fighting female or male dwarves. Oh, wait—am I supposed to say, “little people”? Trust me: Verbiage is not the big problem here. Anyway, regardless of size, women gladiators didn’t wear helmets; the crowds demanded to see loose, flowing, and ultimately bloody hair—who wants helmet head? Worse, the women fought bare-breasted. Just Ow. (Dwarves battling topless women…the term “punching up” comes to mind.)

The really interesting thing, though, is that women gladiators, of which there weren’t that many (more of a boutique taste), did not come from Rome’s lowest, enslaved-and-bedraggled social ranks; most women gladiators came from the working class or better. Why don’t I find it odd that some free (not enslaved) Roman women, devoid as they still were of any rights, would want to strip down, gear up, and hurt somebody?

Blood and Glory

It really isn’t possible for us to judge Romans and their grisly entertainments by modern standards. In fairness, modern life still includes deliberately nasty stuff like dog fights, bull fights, cock fights, mixed martial arts, and boxing matches. And don’t tell me boxing requires strategy and is therefore the “sweet science”—the goal is to punch out the lab equipment.

Rome was an unapologetically martial society. War was their managing metaphor: The path to political power and glory was bloody, opened primarily through military victory, civil war, and assassination. Pompey Magnus, Julius Caesar, Augustus Caesar, Marcus Aurelius, Diocletian, et al had themselves battled to expand the empire or to defend it. Rome didn’t produce the wide flowering of poetry, drama, and philosophy that Greece had, not that Greeks steered clear of war. Instead, Romans emphasized engineering—inventing concrete that cures underwater, building aqueducts, bridges, still-navigable roads, and devising whatever else would promote military maneuvers.

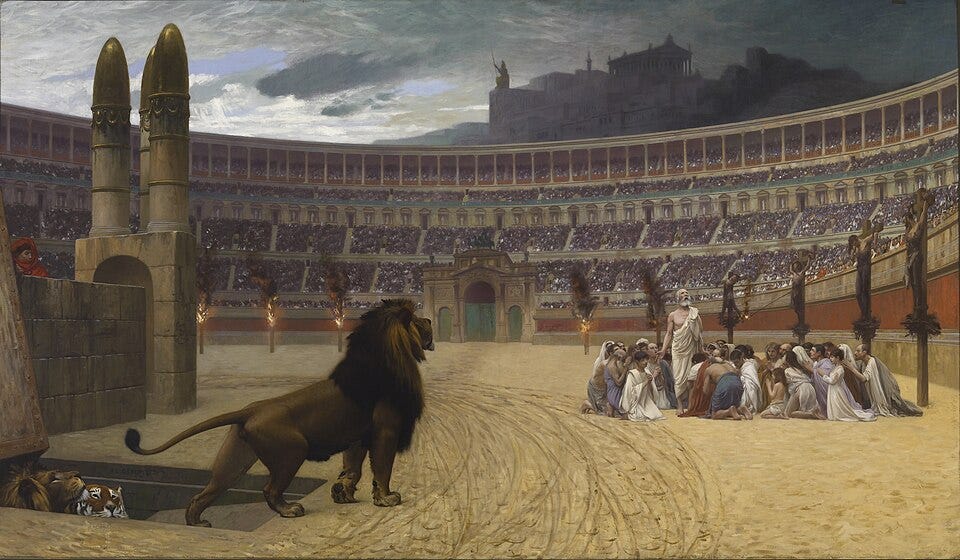

Bleeding and dying in combat were coins of the realm. So when an aristocrat paid out to put on the Games, as was socially expected, and when it was time for the plebs to relax with the whole familia at the arena, that blood and combat became sport. Roman governments also staged arena battles to execute throngs of criminals at a go. It was considered more honorable to die dressed up as a Roman soldier fighting a fellow cosplay criminal. Because ancient Rome had the death penalty—just like not-ancient America.

Residents of Rome and its cities saw blood and death all the time. Bodies got thrown into rivers, the sick and poor collapsed in filthy street corners, crime gangs robbed and murdered, and an estimated one-quarter of babies were abandoned to trash heaps (thanks to patria potestis, the legal power of male family heads to decide who lived and died).

For centuries, blood and gore were also key to Roman religion, which commanded that animals such as cattle, goats, sheep, and doves be frequently and bloodily sacrificed in the temples of the Roman gods. By about 100 CE, blood sacrifice had lost favor. (The Jewish deity demanded animal blood as well, although after Rome’s 70 CE destruction of the Second Temple, the only site where these sacrifices could be offered, the Jews changed the concept of “sacrifice” to mean prayer, study, and ethical behavior. Talk about an improvement.)

Romans might have been accustomed to the nearness of death, but when the Antonine Plague hit, around 165 CE, so many more were dying. Death spread through streets, homes, and military camps, as fast as infected tradesmen, slaves, refugees, and troops moved to and from Rome’s cities and increasingly unstable provinces.

This plague landed in a dangerously hungry Rome as the governmental grain stores drained down. For at least five nervous years before this plague, the Nile had run too low adequately to flood Egypt’s fields and yield the huge shipments of grain that kept Rome fed. Wherever the bug spread, it found vulnerable Romans. Modern scholars haven’t confidently diagnosed the Antonine plague, although some evidence suggests smallpox. It killed slaves, soldiers, plebs, and the emperor, Marcus Aurelius, alike.

So many soldiers succumbed that reinforcements were grabbed from any quarter—marginal barbarians, less qualified men, and over-qualified gladiators. Pressing these top-flight fighters into military service left a large gap in Rome’s line-up of bloody entertainments.

Are You Not Entertained? Part 2 of 2

Just FYI—this happened in Roman provinces, but never in the Roman Colosseum.

Next: Christians tended the sick and filled in for entertainment. Can the promise of an afterlife conquer contagion and death?